Brazil's economy

After the election, the reckoning

BRAZIL is not the only emerging economy facing headwinds (see article

in this week’s print edition). But it is looking particularly wonky.

Having narrowly won a second presidential term on October 26th, this

week Dilma Rousseff returned from a spot of post-election R&R to a

raft of bad news. The trade deficit widened to $1.1 billion in October,

the highest-ever for the month. It now stands at $1.8 billion so far

this year. Both imports and exports fell, pointing to weak activity. An

expected uptick in September’s industrial production turned out instead

to have been a dip; it has now shrunk for five straight quarters.

Then, on November 5th, it emerged that the ranks of desperately poor Brazilians, unable to afford enough calories to avoid malnutrition, swelled by 371,000 between 2012 and 2013, to 10.4m. This is the first increase since Ms Rousseff’s Workers’ Party (PT) came to power in 2003. It comes as a particular blow to the president, who spent much of the campaign boasting of how much she had done to improve the lot of the indigent. Now it appears that, as the opposition has repeatedly pointed out, social progress under Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, who ran the country in 2003-10, has stalled under his protégée.

Experts pin the rise in extreme poverty on sagging output, which affects incomes, and high inflation, which eats into them. And things could get worse. In 2013 the economy grew by 2.3%; forecasts suggest it may not grow at all this year and by around 1% in 2015. GDP per person will drop. Inflation, it is true, edged down in October, to 6.6%, but remains stubbornly above the Central Bank’s target range.

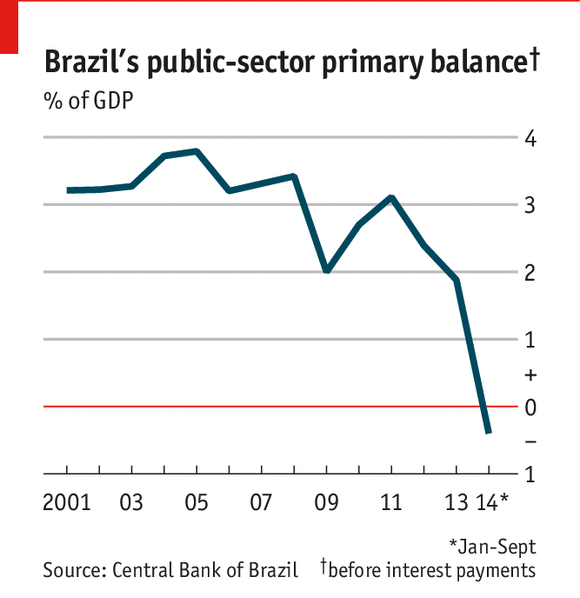

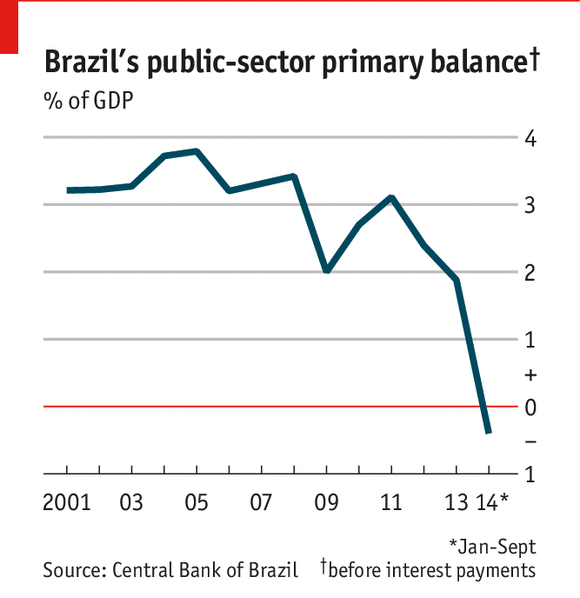

To revive growth Ms Rousseff needs to restore credibility lost

after four years of erratic meddling in the private sector coupled with

monetary and fiscal incontinence. In part as a result of a pre-election

splurge, spending has grown twice as fast as revenues so far this year.

Figures released last week showed a budgetary hole equal to 4.9% of GDP

in the 12 months to September, a 12-year high. In the first nine months

of the year the primary balance (before interest payments) posted the

first deficit since the Central Bank began taking stock in 2001 (see

chart). The government has at last conceded it will miss a self-imposed

target of 1.9% primary surplus for 2014.

To revive growth Ms Rousseff needs to restore credibility lost

after four years of erratic meddling in the private sector coupled with

monetary and fiscal incontinence. In part as a result of a pre-election

splurge, spending has grown twice as fast as revenues so far this year.

Figures released last week showed a budgetary hole equal to 4.9% of GDP

in the 12 months to September, a 12-year high. In the first nine months

of the year the primary balance (before interest payments) posted the

first deficit since the Central Bank began taking stock in 2001 (see

chart). The government has at last conceded it will miss a self-imposed

target of 1.9% primary surplus for 2014.

Optimists hope that the monetary-policy committee’s unexpected decision last week to raise interest rates signals a new willingness on Ms Rousseff’s part to make peace with economic orthodoxy—in particular, to grant the Central Bank more independence to fight price rises. So, they maintain, does the promise made on November 7th by outgoing finance minister, Guido Mantega, to cut spending and restore a primary surplus in 2015—crucial if Brazil is not to lose its cherished investment grade, secured by Lula in 2008.

Cynics note that the interest-rate rise, which was overdue, came only after Ms Rousseff's market-friendly rival for the presidency was dispatched. Although to his credit Mr Mantega pointed to areas like heritable pensions and subsidised loans dished out by Brazil’s huge development bank as ripe for pruning, he did not say where exactly spending would be cut or by how much. To the dismay of markets, Ms Rousseff has yet to name Mr Mantega’s replacement, who would be implementing the cuts.

Even if it is sincere, the government’s new-found monetary and fiscal rectitude should thus be taken with caution, for two reasons. First, cutting earmarked expenditure, including on pensions, requires approval from an increasingly unco-operative Congress. As such, warns Alberto Ramos of Goldman Sachs, the axe is likely to fall on investment, which is already piffling by emerging-world standards but over which the government has greater discretion. This may stave off a sovereign downgrade in the short run. But it would damage Brazil’s long-term prospects.

Second, and more important, many doubt Ms Rousseff’s resolve. Most economists agree that a fiscal and monetary adjustment big enough to ensure sustainable future growth would inevitably push unemployment, still near a record low of around 5%, up in the near term. In fact, given the economy’s current frailty, job losses are likely even in the absence of any reforms. In an interview with a clutch of newspapers on November 6th the president insisted painless belt-tightening is possible. This suggests she may unbuckle at the first hint of discomfort. Any temporary relief, however, would come at the cost of chronic economic weakness. Or, if it prompts rating agencies to demote Brazil to junk, possibly even an acute crisis.

Then, on November 5th, it emerged that the ranks of desperately poor Brazilians, unable to afford enough calories to avoid malnutrition, swelled by 371,000 between 2012 and 2013, to 10.4m. This is the first increase since Ms Rousseff’s Workers’ Party (PT) came to power in 2003. It comes as a particular blow to the president, who spent much of the campaign boasting of how much she had done to improve the lot of the indigent. Now it appears that, as the opposition has repeatedly pointed out, social progress under Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, who ran the country in 2003-10, has stalled under his protégée.

Experts pin the rise in extreme poverty on sagging output, which affects incomes, and high inflation, which eats into them. And things could get worse. In 2013 the economy grew by 2.3%; forecasts suggest it may not grow at all this year and by around 1% in 2015. GDP per person will drop. Inflation, it is true, edged down in October, to 6.6%, but remains stubbornly above the Central Bank’s target range.

Optimists hope that the monetary-policy committee’s unexpected decision last week to raise interest rates signals a new willingness on Ms Rousseff’s part to make peace with economic orthodoxy—in particular, to grant the Central Bank more independence to fight price rises. So, they maintain, does the promise made on November 7th by outgoing finance minister, Guido Mantega, to cut spending and restore a primary surplus in 2015—crucial if Brazil is not to lose its cherished investment grade, secured by Lula in 2008.

Cynics note that the interest-rate rise, which was overdue, came only after Ms Rousseff's market-friendly rival for the presidency was dispatched. Although to his credit Mr Mantega pointed to areas like heritable pensions and subsidised loans dished out by Brazil’s huge development bank as ripe for pruning, he did not say where exactly spending would be cut or by how much. To the dismay of markets, Ms Rousseff has yet to name Mr Mantega’s replacement, who would be implementing the cuts.

Even if it is sincere, the government’s new-found monetary and fiscal rectitude should thus be taken with caution, for two reasons. First, cutting earmarked expenditure, including on pensions, requires approval from an increasingly unco-operative Congress. As such, warns Alberto Ramos of Goldman Sachs, the axe is likely to fall on investment, which is already piffling by emerging-world standards but over which the government has greater discretion. This may stave off a sovereign downgrade in the short run. But it would damage Brazil’s long-term prospects.

Second, and more important, many doubt Ms Rousseff’s resolve. Most economists agree that a fiscal and monetary adjustment big enough to ensure sustainable future growth would inevitably push unemployment, still near a record low of around 5%, up in the near term. In fact, given the economy’s current frailty, job losses are likely even in the absence of any reforms. In an interview with a clutch of newspapers on November 6th the president insisted painless belt-tightening is possible. This suggests she may unbuckle at the first hint of discomfort. Any temporary relief, however, would come at the cost of chronic economic weakness. Or, if it prompts rating agencies to demote Brazil to junk, possibly even an acute crisis.

More from The Economist

No comments:

Post a Comment